'The Dental Divide'

The decay of Australia's oral health as treatment becomes harder to access

A smile tells a thousand words.

In Australia, it tells the story of a fragmented dental system with profoundly inequitable access to essential care.

Tooth decay is one of Australia’s most prevalent health problems and in the last 12 months, less than half of Australian adults had a dental check-up.

Poor oral health can affect a person’s general wellbeing, compromise nutrition, exacerbate existing health conditions, increase chances of chronic disease, and even impact pregnancy outcomes.

So why aren’t we visiting the dentist for essential check-ups?

One barrier is cost, with 40% of Australians delaying or not seeing a dentist because they can’t afford it. A quarter of the adults who do visit the dentist are prevented from accessing further recommended treatment because of cost.

Oral health practitioner and associate lecturer at the University of Newcastle, Kelly-Jean Burden, says delaying or avoiding the dentist due to cost has varying repercussions.

Oral health practitioner Kelly-Jean Burden. Image: supplied

Oral health practitioner Kelly-Jean Burden. Image: supplied

“We see increases in emergency dental visits, greater tooth loss or tooth decay, and mental health impacts because of the pain, discomfort, and self-esteem issues that result from having poor oral health.”

How did we end up here?

When the Whitlam government introduced Australia’s first universal healthcare system in 1975, dental care was left out due to cost and political factors.

When the system was reinstated as Medicare by the Hawke government in 1984, dental care still didn’t make the cut.

Experts say the decision contributed to the ‘dental divide’.

85% of dental care is provided by private dental clinics, with 58% of the cost being met directly by patients. Services such as primary medical care leave patients only 11% out-of-pocket under the Medicare scheme.

For those fortunate enough to have private health insurance, there is still an average gap of 54% on dental expenses. The fees charged in private clinics are not regulated and treatment costs vary case to case.

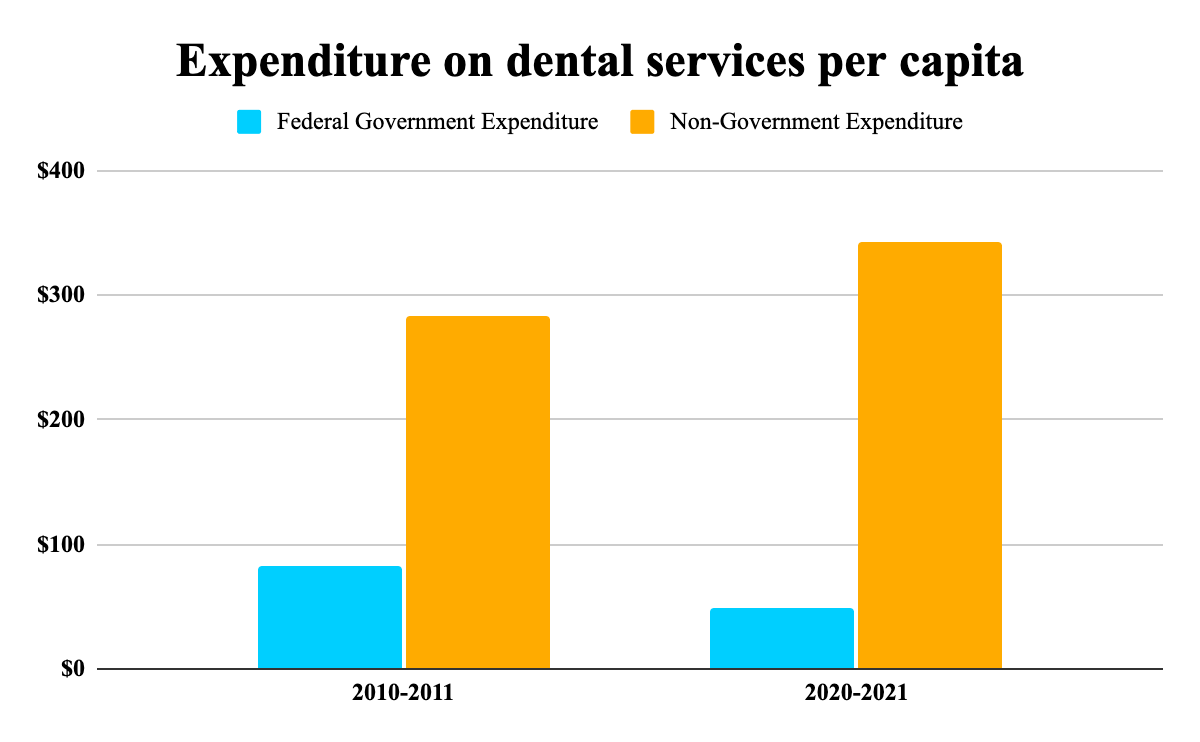

Total average expenditure on dental services shows non-government expenditure, which is made up mostly of individuals, is greater than government expenditure.

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Some Australians have access to services if they hold a healthcare provider card or are under the age of 18 as part of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule.

Burden said despite these services being available, issues prevail.

“We’re generally better than most economically developed countries but it depends obviously on the specific indicators that are used for assessment; so that can be difficult.

“There’s long waiting lists and it’s difficult to be seen because of workforce issues and services available. Not all of Australia has access to fluoridated water, and Indigenous oral health is a problem because access in rural and remote areas is problematic.”

On the wrong side of the dental divide

These barriers to accessing oral healthcare in both the public and private sectors put vulnerable population groups at a greater risk of poor health.

Socially disadvantaged or on low incomes

Burden said there is a clear link between poor oral health and low socioeconomic status.

“There’s a lot of stigma and shame for people. If you’ve got decaying teeth, it can be hard to get a job, so that perpetuates more socioeconomic problems for the person, which I feel is criminal.

"It’s not okay to not give people the opportunity to provide for their family purely because they haven’t been able to access health services that should be accessible to them.”

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

Accessibility of dental services was identified as a big factor contributing to the poor oral health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in the interim report of the Senate Committee into the Provision of and Access to Dental Services released in June.

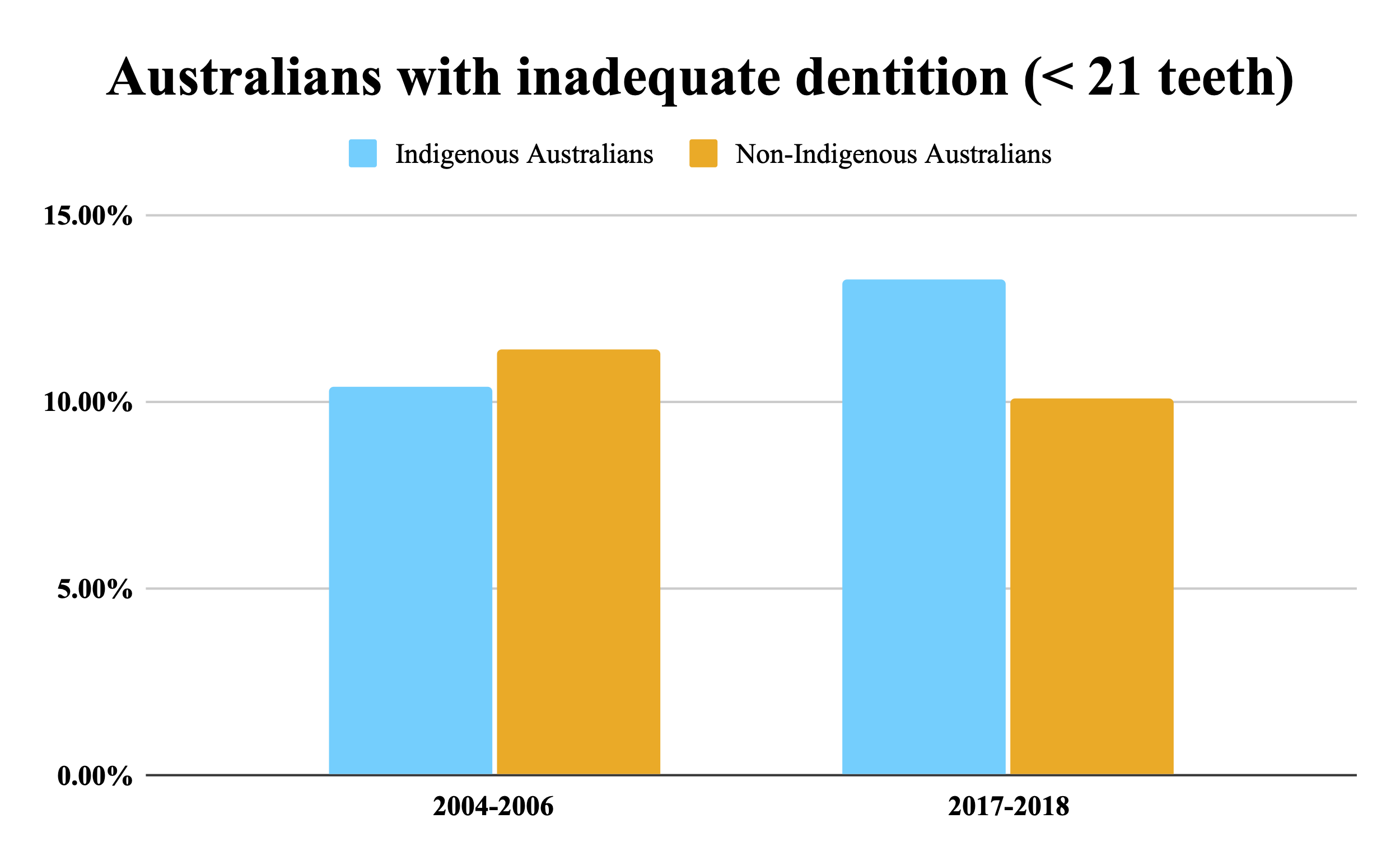

The number of Indigenous Australians with less than 21 teeth increased by almost 3% from 2004 to 2018, while the amount of non-Indigenous Australians with inadequate dentition decreased.

This highlights the widening divide for Indigenous Australians in accessing dental care.

People living in regional, rural, and remote areas

Australians living in regional and remote areas have poorer oral health compared to people living in major cities.

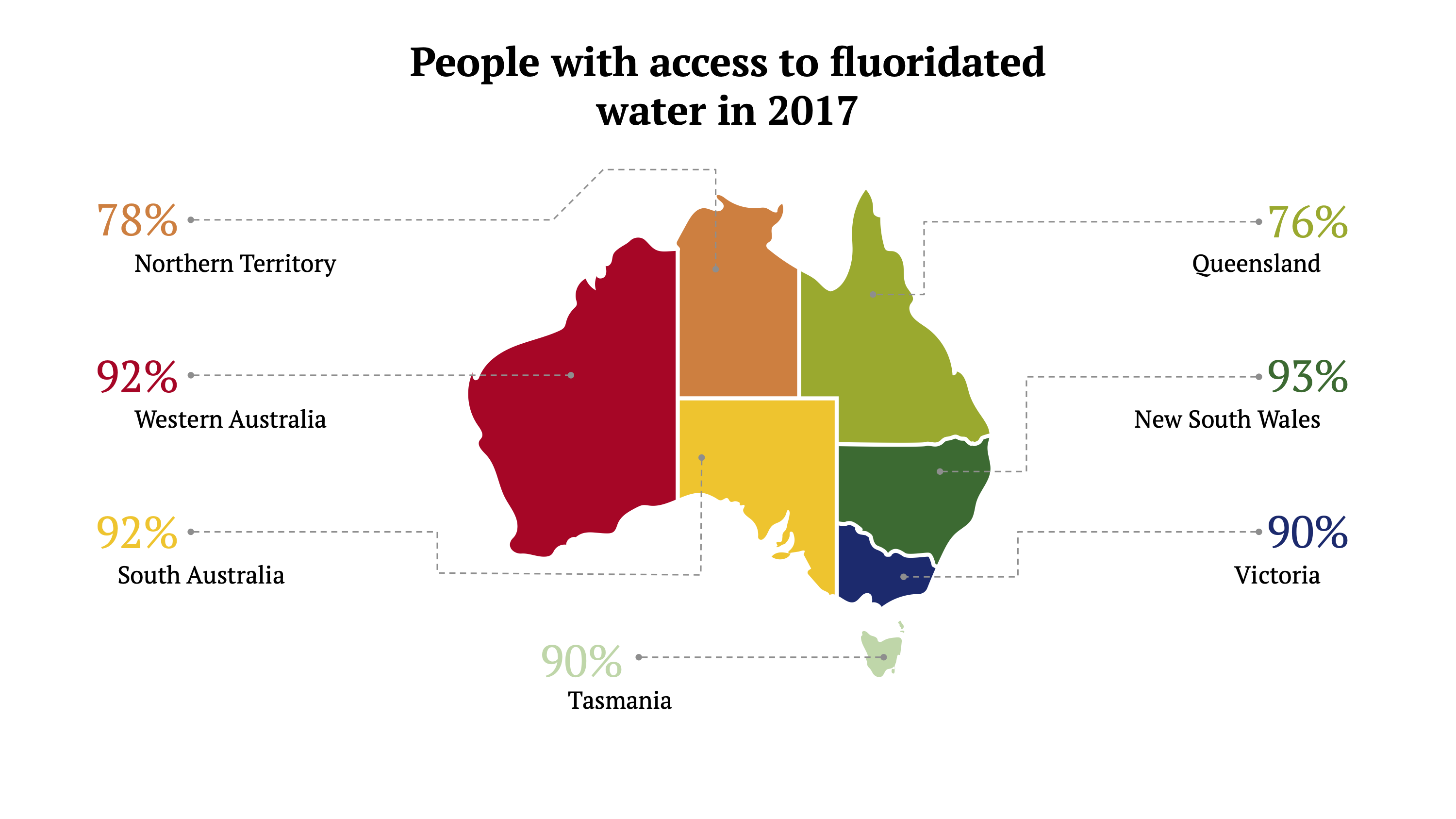

Fluoridated water is a preventative measure which has greatly improved Australia’s dental health, however, people living in rural and remote areas are left out of this strategy.

Reduced access to fluoridated water and a lack of service availability puts these Australians at a significant disadvantage in terms of oral health.

People with additional and/or specialised health care needs

In 2018, 32% of disabled people did not see a dentist due to cost.

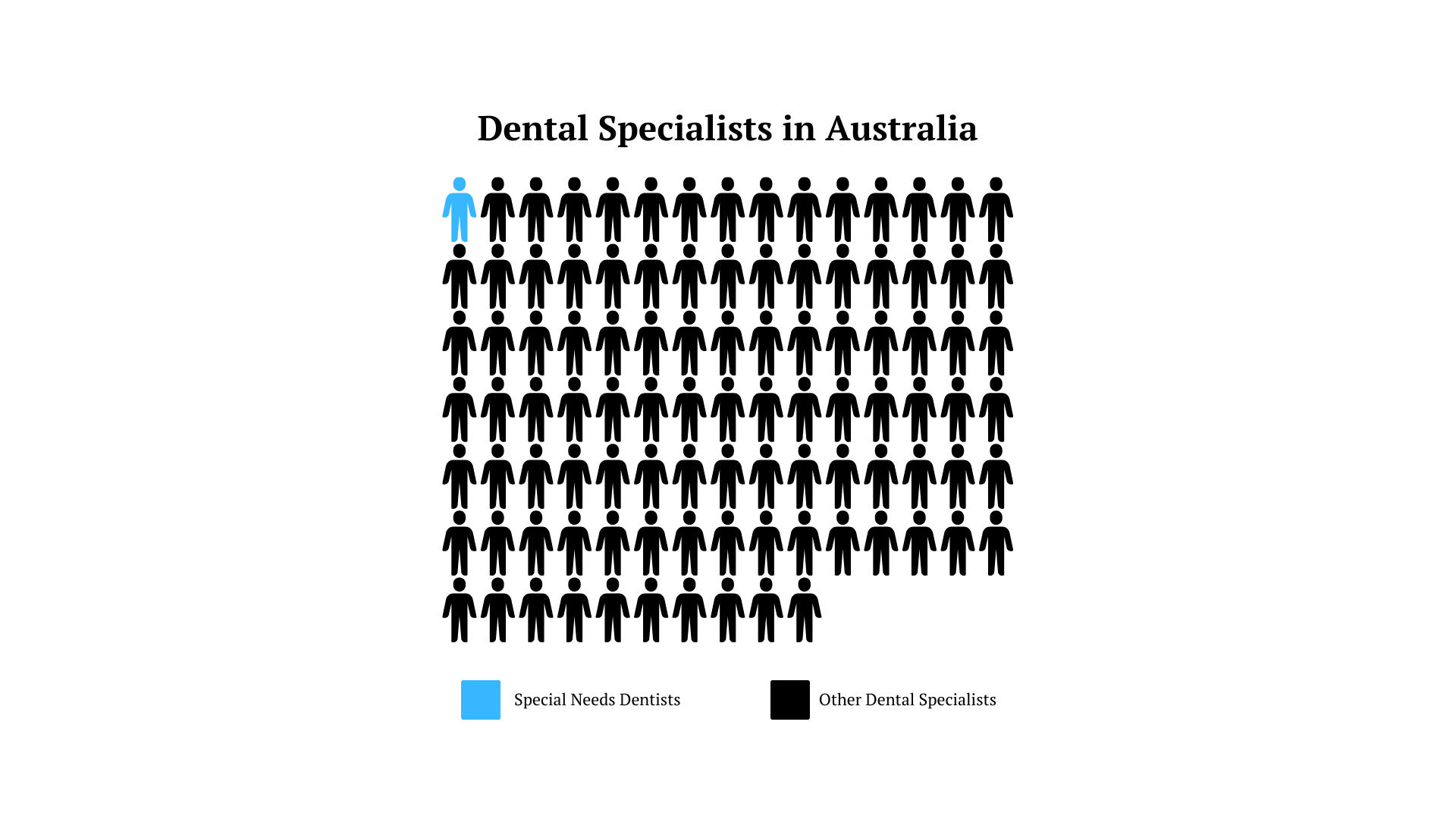

Additional barriers exist as there are only 26 special needs dentists in Australia, amounting to just 1% of dental specialists.

Image: engin akyurt on Unsplash

Image: engin akyurt on Unsplash

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Data Source: Australian Institute of Health & Welfare Graph: Charlotte Wintle

Where to next?

A number of inquiries have been conducted on issues with oral and dental healthcare in Australia with minimal success.

As an expert and advocate for inclusion oral health, Burden identified potential solutions to issues with poor oral health and access to care.

“The expansion of public health services might be part of the solution. More preventative and oral health promotion initiatives are important, and I think they should be based around the inclusion oral health approach where the community is empowered to make the decisions for themselves.

“Public dentistry and things like mobile dental clinics might be something that helps us reach out to those rural and remote communities.”

The Select Committee into the Provision of and Access to Dental Services will make recommendations to the Federal government in its final report set for release on 28 November.

Burden said the resolution to the issue will take some time.

“They’re complicated problems and they’ve been around for a very long time. I can’t tell you there’s an easy solution to them. We’re only just starting to lean into the social sciences to have a greater understanding of the issues; so, we’ve got a long way to go.”